- The first step is making the call.

- 1300 022 482

- hello@searchpartyproperty.com.au

What Does Raising The First Home Buyer Grant Actually Achieve?

With the homeownership dream increasingly out of reach for many Australians, the Queensland government has announced a ‘cost of living boost for first home buyers’—with the first home buyers’ grant being doubled from $15,000 to $30,000. The increase came into effect on the 20th of November and will remain until mid-2025, available for those buying or building a new home worth less than $750,000.

It’s a big policy move, designed to make the market more accessible to first-time buyers.

But of course, we know that poor housing affordability is the result of a complex interaction of factors, so is simply increasing a grant enough to cut the Gordian knot?

Furthermore, could it really be a counterintuitive decision—one that makes affordability worse?

A short-term outcome?

In the very immediate future, there’s no doubt that these policies offer some benefits to first-time buyers. Particularly in terms of building a deposit, these grants make the often-daunting prospect of purchasing a home somewhat more achievable.

Interestingly, the last time we saw a temporary boost to the first home buyer grant was during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. At that time, a first home buyer looking at a new home was eligible for an additional $14,000 (later reduced to an additional $7,000 from the 1st October, 2009) in addition to the standing $7,000 grant.

At least on paper, it looks like this policy did the trick. The number of first home buyers in Queensland surged, recording a 36% increase from October to November 2009 and peaking at an all-time high in April of the same year. As the supplementary amount for new homes was reduced to $7,000 from the initial $14,000 at the end of September 2009, the activity of first home buyers declined and subsequently fell to significantly below average once the additional funding ceased in December 2010.

However, the major issue with such grants remains their long-term impact on the market and short-sighted approach.

In theory, an influx of first-time buyers, empowered by a larger grant, increases demand and drives up prices – especially in entry-level segments of the market. While this benefits current homeowners and investors with increased equity, it poses a worsening situation for future first-time buyers down the track.

Yes, Queensland’s new grant may be restricted to only new homes, but this simply compresses the demand increase into the new home market – making that subset of homes even more expensive.

A look at history

Fortunately, first home buyer grants are not a new idea, and there’s a lengthy history of examples that prove their long-term effect. The first home buyers’ grant was first introduced in Australia as a national scheme in the early 2000s. Originally, it was a response to the introduction of GST, aimed at offsetting the increased cost of new homes. Over time, the concept has been fine-tuned and reimagined, with various states introducing stipulations to suit economic conditions and housing market dynamics.

Last year, the Australian Housing Urban Research Institute published research studying the outcome of the cumulative $20.5 billion (in 2021 money) spent on first home buyers’ grants and other incentives, across the decade preceding 2021:

(SMH, 2022)

The overall finding of this research was that such policies had only worsened generational inequality and housing affordability. Contrasted with policies in Canada, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore, Ireland, and the UK, the report also found that Australia was unique in its approach to bolstering demand-side factors rather than addressing housing supply. Additionally, Australia’s lack of a comprehensive strategic policy framework and minimal progress in addressing the static rate of homeownership were identified as notable cause for concern.

It’s worse than a waste [of money]. It’s money that has gone into making a problem worse… and it ends up going into inflating home values,” said report author Dr Chris Martin.

More recently, the Australian Government’s Productivity Commission also called for an end to first home buyer grants, similarly claiming that they work against improving housing affordability – the very thing they are intended fix.

Furthermore, in a study published by Deakin University in 2012, researchers concluded that first home buyers’ grants, exacerbated by inelastic supply, have a disproportionate impact upon house prices. Across the decade from 2000 to 2010, regression analysis indicated that first home buyers’ grants (then worth just $7000) were alone responsible for a $57,000 increase in property values across Australia. Relative to what median house prices were at the time, this equates to almost a 20% increase in property values.

This effect should theoretically apply today just as it did over 10 years ago.

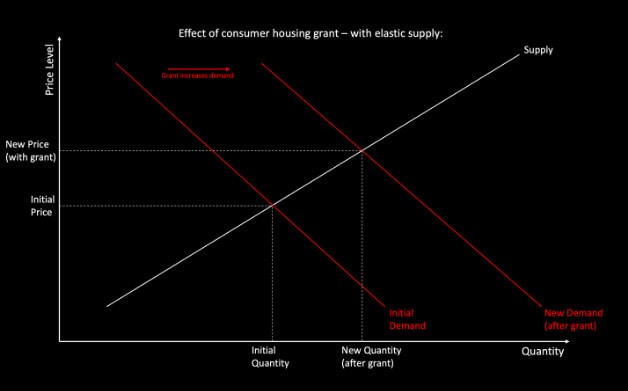

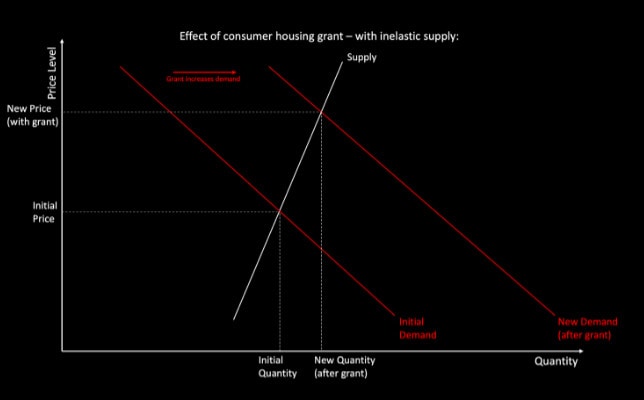

Crucially, if a buyers’ grant typically raises prices by shifting demand, the effect is exaggerated in markets where there is inelastic supply – in other words, if new housing construction is unable to keep up with the demand:

As you can see in the above charts, the same increase in demand can have a much larger impact upon prices when supply is more inelastic (as the second graph illustrates with the steeper curve).

Due to high immigration figures and soaring construction costs, the reality of Australia’s inelastic housing supply doesn’t seem likely to change. This fact is supported by the Real Estate Institute of Queensland, who in response to the new grant’s announcement were quick to point out exactly that: “Builders in Queensland are already facing the highest construction costs in the country, and we would expect this measure to drive up those costs further.

”It all indicates that, for new homes in particular, the effect of this larger grant upon prices could be bigger than ever.

Want to discuss this further?

For expert guidance in property strategy, and what it could mean for you as a property investor, book in for a free consultation to make informed decisions, tailored to your investment goals. Don’t let affordability challenges hinder your success. Act now with Search Party Property!