- The first step is making the call.

- 1300 022 482

- hello@searchpartyproperty.com.au

Will Australia’s New Housing Policy Be Effective?

A couple of weeks ago, the media was abuzz with reports of a new housing policy discussed at a meeting of the national cabinet in Brisbane. Alongside state leaders, the Prime Minister announced ‘a better deal for renters’ via a $3 billion assault on perceived low housing supply.

“All governments recognise the best way to ensure that more Australians have a safe and affordable place to call home is to boost housing supply,” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said in the announcement.

Some of the key proposals announced include:

1. Measures to limit rental increases to once a year.

2. A national policy on evictions, requiring more extensive criteria for eviction.

3. A new national planning reform blueprint, which would look at streamlining planning and zoning measures to increase housing supply.

4. An incentive of $15,000 for each additional new home constructed by the states and territories, in addition to the allocation of 1 million well-located homes, resulting in a total of $3 billion in incentive payments.

These announcements come amidst a severe projected housing shortfall, which many experts are blaming for the rapid decline in housing affordability and the ongoing rental crisis.

The ABS continues to report significant declines in the rates of home ownership over the past ten years, and the prospect of purchasing a home has become so distant that two-thirds of aspiring homebuyers believe their only viable path to purchase lies in receiving an inheritance (Australian Institute, 2023). Those who are unable to secure a purchase find themselves locked in the rental sector, grappling with exorbitant rents for substandard and unstable accommodation.

So, with an awful lot riding on these initiatives – how likely are they to slow the market and improve affordability for Australians? And as always, what are the potential implications for investors?

To answer that, let’s assess a couple of the criticisms levelled at the government’s new proposals:

1. Rental Caps

The plan to limit rental rises to once per year seems fairly logical. If rents are already too high for many to afford, then it makes sense that we might wish to slow the rate of increase. In fact, some have responded critically to these proposed measures for not going far enough, with the Greens calling for an overall cap on rents in addition to at least a 2-year freeze on rental increases (ABC, 2023).

However, the real outcome from rental caps may end up being contrary to the intended effects.

According to Brendan Coates, an Economist with the Grattan Institute in Melbourne, “While it may seem attractive to renters facing steep rent rises, [rental caps] end up doing more harm than good” (Sydney Morning Herald, 2023). Like many experts, Mr Coates warns of a decline in investment arising from rental caps, which would reduce housing supply into the future and only worsen affordability.

Importantly, rental cap policies aren’t a new concept and several overseas studies have assessed their impact.

One such study of San Francisco’s housing market revealed that while rent control initially prevents displacement and decreases mobility among renters by 20%, it also results in a 15% reduction in long-term rental housing supply. Furthermore, in another study of similar policies in New York, properties subject to rental caps were found to be more at risk of being dilapidated and under maintained by landlords. Thus, rental caps could end up being bad news for renters and property investors alike.

2. The Focus on Supply

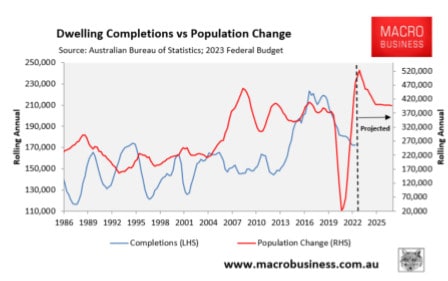

Along with rental caps, the emphasis upon supply as the underlying issue has drawn criticism. Many commentators, such as MarcoBusiness economist Leith Van Onselen, have pointed to indicators such as new home sales, dwelling approvals, and owner-occupier finance commitments – which all show significant declines.

It suggests a bleak forecast for future housing supply, with decade-low levels of home building on the horizon for 2024, high interest rates, and a continued reduction in overall construction activity across the next few years. Furthermore, Oxford Economics Australia have predicted a 21% decline in overall dwelling construction activity, leading into 2025. Australia has also only once constructed more than 220,000 new homes in a year (2017), so the government’s target of 1.2 million homes in 5 years is certainly ambitious – especially for what is already a high performing nation in terms of global housing supply.

However, perhaps contrary to the government’s messaging on housing policy, Australia can actually be regarded as a world leader in housing construction. In 2020 (the most recent year of comparison), Australia held the 4th highest share of new home construction compared to other OECD nations. Indeed, many prominent voices are suggesting the core of Australia’s housing crisis is not low supply but rather high demand.

In a recent report, Louis Christopher of SQM Research blamed “rampant population growth” for Australia’s rental crisis:

“Clearly, acute rental shortages remain with us. And besides more people grouping together to share the burden, there is no significant solution on the horizon”.

“Australia currently has, by far, the fastest growing population for any OECD country and clearly the rampant increases are currently breaching the country’s capacity to house all our people”.

Budget forecasts indicate net overseas migration to peak at an unprecedented 400,000 in 2022-23, tapering to 315,000 in 2023-24, and eventually stabilizing at a historically high level of 260,000 throughout the years following.

Ostensibly, the sudden increase in immigration figures are a compensation for the Covid-19 border closures and the lack of immigration in that period. However, as we’ve explored in a prior article, one feature of the pandemic was a sharp decrease in household size. This change produced an increase in overall market demand equivalent to the demand that would otherwise have been created by immigration. Thus, the decision to now significantly raise immigration is highly unnecessary (at least in terms of the housing market) and will have an extreme effect on the affordability issues that the government is attempting to address.

Where does this leave investors?

All things considered, cabinet’s plan to tackle Australia’s housing crisis presents is a complex set of proposals that doesn’t seem likely to fully address the underlying issues. While the intent to increase housing supply and make rental living more manageable is laudable, the potential consequences of rental caps and the ambitious targets for new home construction raise serious concerns. With immigration remaining at a level that will seriously exacerbate demand, the effectiveness of the proposals seems doubtful. A major market contraction seems unlikely to happen any time soon.

Nevertheless, investors should continue to watch closely, and the coming years will reveal whether these measures truly align with Australia’s unique housing landscape or if they fall short of providing a solution to the affordability crisis.

Want to discuss this further?

For expert guidance in the implications of Australia’s new housing policy, and what it could mean for you as a property investor, book in for a free consultation to make informed decisions, tailored to your investment goals. Don’t let affordability challenges hinder your success. Act now with Search Party Property!